Piracy battles have ISPs stuck in crossfire

As Napster's heyday fades into Internet mythology, its influence is being etched in an

increasingly tense game of cops and robbers that has Internet service providers caught in the

crossfire.

ISPs are stuck in an uncomfortable digital dragnet as record companies, Hollywood studios and

independent copyright bounty hunters target their subscribers as pirates. Increasingly, service

providers are even being asked to cut their subscribers' connections, a last-ditch proposition that

these companies ordinarily avoid at all costs.

Although many ISPs are complying, several of the largest are putting the brakes on the most severe

of these requests, saying copyright law simply doesn't cover the new file-swapping services. The

resulting tension outlines what will likely be an increasingly contentious battlefield as file trading

shifts from centralized services such as Napster to new networks such as Gnutella and others that

can be approached only one individual at a time.

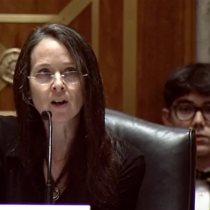

The new file-swapping services "can't fit under the (copyright law), and the copyright community is

very frustrated," said Sarah Deutsch, associate general counsel for Verizon Communications, one

of the biggest high-speed ISPs. "It's one thing to ask us to take material down. But asking for

subscriber termination is a very drastic remedy that infringes on people's rights and speech."

The run-ins over individual subscribers' actions and what to do with them are just part of a broader

tug-of-war being played out between ISPs and copyright holders around the world.

This weekend, diplomats and corporate representatives will meet to negotiate a new treaty on

international law, parts of which ISPs warn could badly undermine a hard-fought balance in the

United States that shields them from financial liability for their subscribers' actions. With the new

implications of Napster and its descendants, those diplomatic discussions are reopening painful

memories of the massive Washington, D.C, lobbying battle between media and

telecommunications companies that gave rise to current U.S. law.

Piracy's Prometheus

A few high-profile ISP enforcement actions have already emerged, as record labels and Hollywood

studios separately mount campaigns to shut down file traders. A few individuals have been publicly

targeted for trading works, including an Oklahoma University student who's PC was confiscated by

school authorities after the record industry complained about Napster use.

In addition, the past few weeks have seen a surge in alliances from a new generation of

piracy-hunting companies, underscoring the now-permanent nature of the cat-and-mouse game.

Napster itself is fading from the radar screen as the hub of online file-trading, these companies

say. But, they add, the massive publicity stemming from the site's popularity and the record

companies' lawsuit against it has left a lasting legacy: The mainstream public knows copyrighted

material is freely available online.

"The general public is becoming more and more aware that this stuff is out there," said David

Powell, CEO of Copyright Control, one of the oldest copyright-hunters on the Net. "Piracy is

increasing very rapidly."

The tactics pursued by individual companies such as Copyright Control, Copyright.net and others

are similar to those of the record and movie companies. Each has the technology, either in-house

or from outside consultants, to search through networks such Napster, Gnutella or Aimster and find

the Net addresses of computers sharing files.

This technology doesn't reveal individual subscribers' names, but it can be used--if the ISP

agrees--to trace an individual.

Previously, most piracy requests asked an ISP to take content off the Web or off its server. This is

explicitly covered by copyright law and has not been overly controversial. But in the peer-to-peer

world, copyrighted works are on subscribers' hard drives, which ISPs can't control.

In this area, the tactics reach into disputed territory. The most ambitious copyright policers, which

ISPs say tend to be the independent companies, are asking that subscribers' be cut off. And that's

where some ISPs are balking.

Everybody wins, sort of

Some of this initial tension has begun to die down. Dave McClure, executive director of the United

States Internet Industry Association, says that he has heard few complaints from member ISPs in

recent weeks, a change from several months ago.

The copyright enforcers say they are doing their best to work with the ISPs to balance interests.

"They've got businesses to run," said Cary Sherman, the Recording Industry Association of

America's general counsel. "We have to be sensitive in terms of asking them to do things that

would be harmful to their business."

Anti-piracy scouts have taken a tack that works with some ISPs, noting that people exchanging huge

volumes of illegally copied movies, songs or software use far more bandwidth than ordinary

customers, making them expensive to serve. New broadband customers are costly to find and

keep, often requiring several years for ISPs to make up the initial expense of discounted equipment

and other sign-up bonuses. But the savings on bandwidth makes cutting off these subscribers

worthwhile, companies such as Copyright Control argue.

ISPs also have terms of service that almost universally bar copyright violations. Many copyright

protectors have presented what they say is ample evidence of the violations.

This has led in some cases to more amicable relationships between ISPs and the piracy patrols.

But resistance from large ISPs including Verizon, EarthLink and others is forcing an issue that

courts ultimately may need to rule on: Are individual file-swappers violating copyright law?

"That issue has never been litigated before," Verizon's Deutsch noted.

Outside these individual flare-ups, the ISP community is preparing for the prospect of broader policy

battles. The international debates over the Hague Convention on International Jurisdiction and

Enforcement of Foreign Judgments is the current concern, as service providers worry that their U.S.

protections will be undermined.

But some worry that even U.S. debates might be reopened as more people sign up for broadband

connections and discover file swapping.

The RIAA's Sherman said his organization, one of the biggest copyright holder lobbying groups, is

happy with existing law for now. Wary ISPs are nevertheless on the lookout for signs of change.

Copyright holders are "putting out tremendous amounts of money on enforcement actions that they

can't recover" from ordinary individuals, the U.S. Internet Industry Association's McClure said. "That

means they have to find somebody with deep pockets that they have to go after. And that's ISPs."