RAMBUS : A Hot Stock's Dirty Secret

As attempted billion-dollar heists go, this one was unobtrusive. There wasn't a pile of cash in the room or a trove of jewels stashed in a vault. The target was far more ethereal. Inside a banquet room at the Crystal City Stouffer Hotel outside Washington, D.C., a computer industry committee was debating elements of a new standard for memory chips. As happens in these settings, heavyweight competitors--IBM, Hewlett-Packard, Samsung, and Toshiba among them--were working together to decide the shape of the next generation of chips.

Also present at those mid-September meetings in 1992 were two representatives from a tiny technology-design company called Rambus. They listened as their industry colleagues discussed an element known, in typically impenetrable techno-gibberish, as "programmable CAS latency." A week after the meeting, one of the two Rambus staffers, Richard Crisp, met with a company attorney to talk about amending Rambus' pending patent applications. Among the new technologies that Crisp wanted to add: programmable latency. A few months before, Crisp had recommended adding patent claims for "mode registers"--right after they were debated at the same standards committee. Only a few months before that, it was "low-voltage swing." All those technologies made the same quiet journey from the standards committee agenda into Rambus patent applications.

Nearly a decade later, long after the standards had been adopted, Rambus--a Los Altos, Calif., company with 175 employees and $72 million in revenues--decided it was time to cash in. In late 1999, citing its patents, which by then had been issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, it began demanding royalties on technology that represents 80% of the $32 billion market for chips known as dynamic random-access memory (DRAM). Incredibly, Rambus--which designs its own version of DRAM technology--was attempting to claim ownership of a competing DRAM design, one that Rambus had long maligned as inferior. Rambus' design was a Ferrari, to use the company's own analogy; its competition a Volkswagen. Rambus wanted to be paid not just for the Ferraris, but also for the Volkswagens.

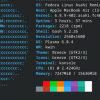

That audacious strategy is now backfiring spectacularly. Hailed as "the year's hottest IPO" by the Wall Street Journal after it went public in 1997, Rambus' stock was long a favorite of chat-room denizens and CNBC devotees. But Rambus is spending a hefty portion of its revenues as it battles its way through 11 separate patent-related lawsuits in the U.S. and Europe against three much larger, wealthier opponents. In the first case to go to trial, this past May, Rambus was soundly trounced; a jury in Richmond found that the company had defrauded Infineon, a spinoff of German giant Siemens. Though Rambus declined interview requests (and would answer only a handful of questions via e-mail), a review of 3,000 pages of transcripts and exhibits from the trial shows that the company plotted to gather patents on standardized technology for years, even as it participated in a standards committee that requires companies to disclose their patents. It's no surprise, then, that Rambus stock has plummeted more than 90% from its June 2000 peak.

Tales of company downfalls have become depressingly familiar in the past few years, of course. But Rambus is no flaky dot-com. It's a profitable chip-technology designer with a signature product blessed by Intel, whose elite Pentium 4 chips currently uses only Rambus technology. No, Rambus' problems have come not from the passing of an economic bubble but from its embrace of two age-old sins: duplicity and greed.

Rambus always had plenty going for it. It was founded in 1990 to solve a critical problem in computer technology. The speed of microprocessors, which crunch data, had improved so quickly that they far exceeded the rate at which memory chips could provide that data. Founders Mike Farmwald and Mark Horowitz, both Stanford Ph.D.s, invented a way to connect the two types of chips that would dramatically improve the speed at which data could be moved from memory to microprocessors. Farmwald and Horowitz had no desire to raise $1 billion to build a chip-fabrication facility, however. Instead, they set up shop as an intellectual-property company. They would sell their technology to chip manufacturers and make money on royalties and consulting fees. They called their technology RDRAM.

By all accounts, RDRAM was a giant leap forward. But selling it proved no easy task. It was so different from past incarnations of memory technology--and so much faster--that chipmakers at first doubted it could work. It was expensive to implement. And the very chipmakers to which Rambus was trying to sell its products were developing a competing product called SDRAM. Where RDRAM was seen as revolutionary, SDRAM was resolutely evolutionary. (The most significant difference between the two, according to the judge's ruling in the Infineon trial: RDRAM transmits three different types of information on a single "bus"--essentially a collection of wires; SDRAM has separate buses, each dedicated to a single type of information.)

In a June 1992 business plan, Rambus CEO Geoffrey Tate described the SDRAM as generally "inferior" and dismissed it as an "incremental improvement" on 20-year-old technology. Still, he noted, "all customers are familiar with it and understand it, so there will be a tendency to try the Sync DRAM [SDRAM] approach."

Tate laid out a four-part strategy for dealing with the SDRAM threat. The first three parts assessed ways in which Rambus could "counter" the technology in the market. Part four laid out a parallel strategy, to claim ownership of it: "We believe that Sync DRAMs infringe on some claims in our filed patents; and that there are additional claims we can file for our patents that cover features of Sync DRAMs. Then we will be in a position to request patent licensing [fees and royalties] from any manufacturer of Sync DRAMs." Rambus would follow that plan to a tee--competing with SDRAM in public while quietly working to lock up the patent rights to key parts of it.